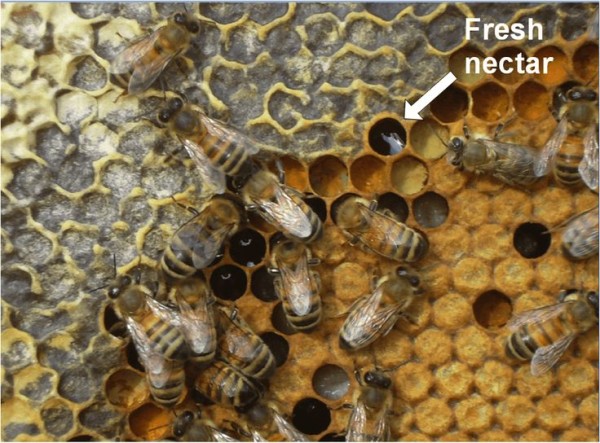

This is the time of year when swarming starts to happen. Bees are triggered to swarm when the hive becomes crowded—especially with sealed brood, abundant pollen, plenty of capped honey, and fresh nectar filling the brood cells. This last condition, known as backfilling, initiates the swarming impulse. Be sure to monitor areas where fresh nectar is pushing into the brood area. (See Photo)

Another early sign is the appearance of queen cups. Colonies often build many of these as a preliminary step toward either swarming or supersedure, but they may not use them. It’s when you see larvae and royal jelly inside the cups that it becomes serious—that means the colony has moved into phase two. The location of the queen cells often signals the colony’s intent:

• Swarm cells are usually found on the bottom of the frames.

• Supersedure cells are typically located mid-frame.

Once the first queen cell is capped, colonies tend to swarm shortly after. Swarming is most successful when it occurs early in the season—on the uphill slope of the pollen flow—before the main nectar flow begins.

To reduce swarming pressure, make sure there are always plenty of open cells in the broodnest. The goal is to trick the colony into thinking it still has room to grow, not swarm. That means keeping the broodnest from becoming congested. You can do this by making drawn comb available within, above, or next to the broodnest. (Note: Only add drawn foundation, adding undrawn foundation is not the same!)

One effective technique is checkerboarding, which involves inserting drawn comb above the broodnest throughout the honey band. You may need to remove some outside honey frames to do this properly.

There are many methods for swarm prevention, but the most reliable is to check weekly for signs of backfilling—it’s usually the first clue. Overwintered colonies are much more likely to swarm than new packages or nucs.